Community, Leadership, Experimentation, Diversity, & Education

Pittsburgh Arts, Regional Theatre, New Work, Producing, Copyright, Labor Unions,

New Products, Coping Skills, J-O-Bs...

Theatre industry news, University & School of Drama Announcements, plus occasional course support for

Carnegie Mellon School of Drama Faculty, Staff, Students, and Alumni.

CMU School of Drama

Friday, March 06, 2020

Gain Without the Pain: Gain Structure for Live Sound Part 2

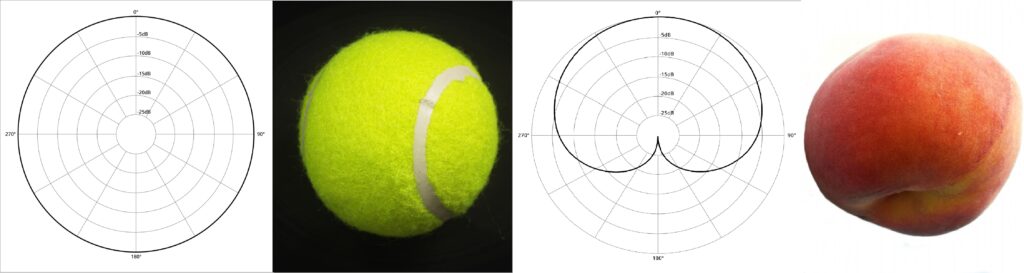

SoundGirls.org: I like to think of gain as a tennis ball growing out of the mic if it’s omnidirectional, or a peach for cardioid mics, with the stalk-socket (is there a word for that?) at the point of most rejection. Bidirectional/figure eight mics always remind me of Princess Leia’s famous hair buns in Star Wars. Whatever you imagine it as, don’t forget that the pick up pattern is three dimensional. There can be a bit of a subconscious tendency to think of pick up patterns as the flat discs you see in polar plots, so don’t fall into that trap!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

I feel like in this day and age we can forget that solutions to many of our problems can actually be quite simple, and don't need all the cutting-edge technology we have. For example, a well structured gain partnered with simple EQ on your audio channels will do wonders to your sound without the need for crazy compression or other fancy plugins or inserts. I particularly like the note about plosives, and that all we really need to do is get the mic out of the way of the line of (air) fire. I've seen engineers try to deal with this at the console, which can ultimately affect things further down the line. This brings up an even broader point about the structure of your 'critical path', which is try to do it right early in the signal or process instead of constantly chasing and correcting errors like a cruel game of whack-a-mole. In scenery, taking the time to properly plan out a production from the moment it hits our desk for budgeting can work wonders weeks later when it is being built on the floor. This article can give us insight not only into using simple gain structures to solve problems, but also a better way to approach problem solving.

I feel like in this day and age we can forget that solutions to many of our problems can actually be quite simple, and don't need all the cutting-edge technology we have. For example, a well structured gain partnered with simple EQ on your audio channels will do wonders to your sound without the need for crazy compression or other fancy plugins or inserts. I particularly like the note about plosives, and that all we really need to do is get the mic out of the way of the line of (air) fire. I've seen engineers try to deal with this at the console, which can ultimately affect things further down the line. This brings up an even broader point about the structure of your 'critical path', which is try to do it right early in the signal or process instead of constantly chasing and correcting errors like a cruel game of whack-a-mole. In scenery, taking the time to properly plan out a production from the moment it hits our desk for budgeting can work wonders weeks later when it is being built on the floor. This article can give us insight not only into using simple gain structures to solve problems, but also a better way to approach problem solving.

Learning how to think about gain structure is a relatively simple lesson for those interested in sound, but so often it is overlooked. Often, the first things that sound people are taught is what different pieces of equipment are, and how to set up some certain sound system. There often is a lack of 'why.' Understanding gain structure and how different problems arise can be much more useful. Saying that a system 'should' have a compressor is much less useful for someone getting into sound than saying 'you want an equal volume level, but the speaker might move around a lot. You could just ride the fader, but that's dependent on your reaction time. If you use a compressor, you can make the equipment's reaction time the relavent interval.' That's actually helpful and it allows the person to apply that knowledge to other novel situations. Problem solving is half of the job. This article is a good example of how to teach for learning to think that way.

Post a Comment